A couple of poems

A very fine actor

Is Alfred Molina.

A place for your tractor

Is South Carolina.

History must judge

Cornelius Fudge.

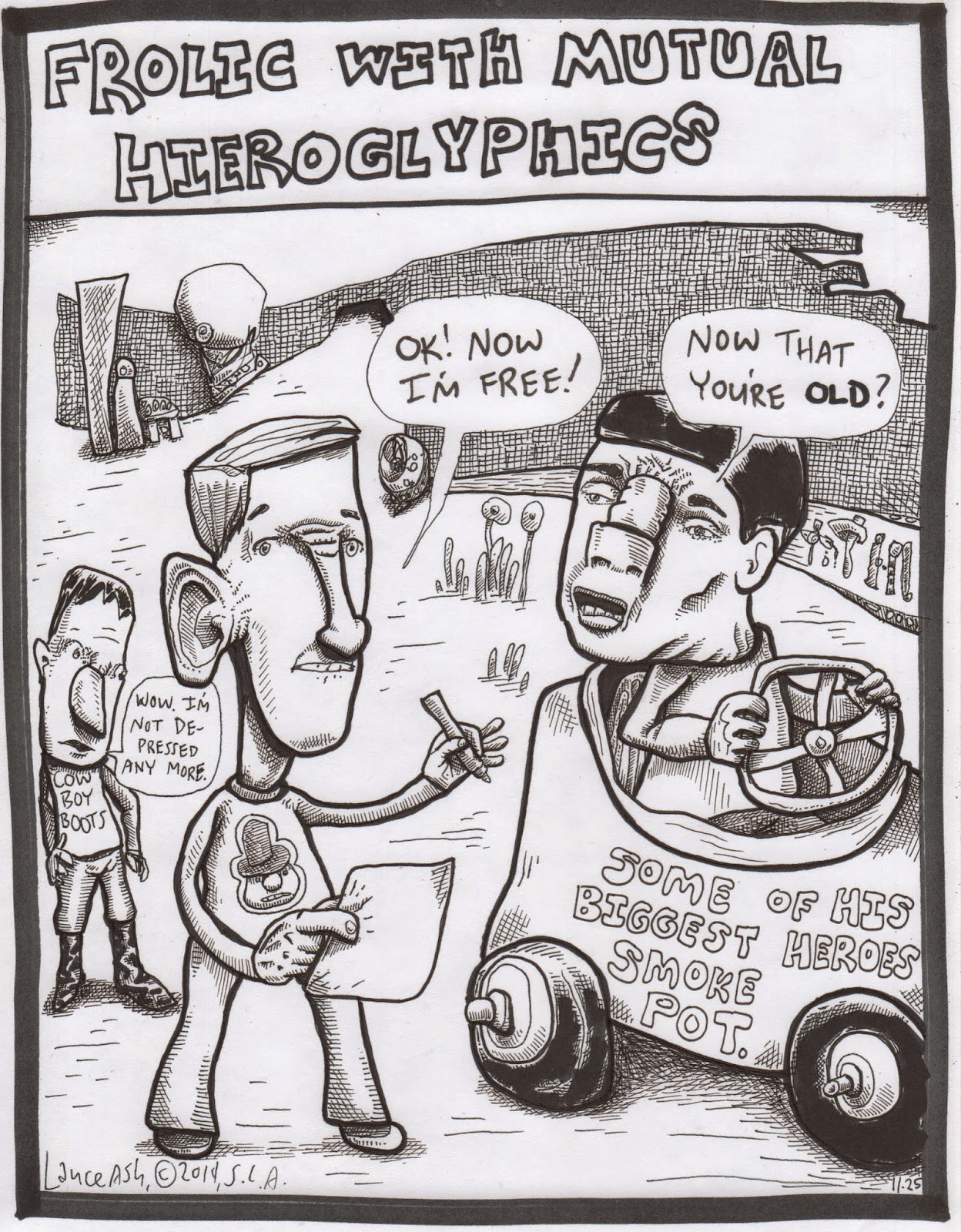

Frolic with Mutual Hieroglyphics

Frolic with Mutual

Hieroglyphics

Pigmented

frost saturated the sides of Mr. Lurie’s art project. As he and a crowd of assistants and

sycophants stood about, debating what to do to correct the situation, the

gallery’s curator, Mr. Moore, emerged from his office onto the catwalk

overlooking the gallery floor.

“Come take

a look at this,” he called to me, his forearms on the railing.

“He calls

it the Sardine Stethoscope,” Moore informed me. I carried my mug of fancy green tea out of

the office and joined Moore

at the railing.

“I’m a

hypocrite,” I told Moore . “As we all are, naturally. I resent such indulgent tripe even as I am

guilty of doing the same type stuff.”

“Surely you

can’t compare your work with this.” Mr.

Moore bounced his forehead towards the installation, which was a large,

fabric-covered box.

“If you

don’t like it, then why do you have it in your gallery?”

“First of

all, it’s not my gallery; I’m just the curator. Second, I like Lurie; he’s a good guy,

even if his art is crap. Third, he’s a

famous name. If a Mr. Lurie wants to

spend his time between albums doing this sort of thing,” again Moore used his forehead as an unobtrusive

index finger, “Then his work acquires value, even if it’s only the value of

notoriety.”

I felt that

my tea was cool enough to drink. I had

never tried Patriot’s Umbrella. It was

supposed to be good; at least, according to an article in Samsasamsara magazine that

someone had told me about.

“How is

it?” Mr. Moore asked, smiling at my face of disgust.

“It has

tremendous snob appeal,” I replied, so tempted to dump the rest of my mug onto

the Sardine Stethoscope that I had to

cast my mind into a reverie to stop myself.

Ten years

earlier I was working at the Post Office, hoping that the facility I worked at

wouldn’t be shut down and my job transferred to a larger one in Atlanta , necessitating a

one-way commute of two hours. There

were those that I worked with who didn’t care if we were all shipped off the Atlanta : they either lived

in rental properties and could easily move closer to work or they didn’t have a

multi-faceted art career demanding a couple hours’ attention every day as I

did. I was a painter, a writer, a

cartoonist, and a musician. I felt that

everything depended on the maintenance of the routine I had established. Without my art, the many things that I did,

my life would be empty. I might as well

start going to church or take up drinking again.

Ten years

earlier the sunburst medallion given to me by the Fromme Emperor shrank to the

size of a soybean under the glare of the roadside halogens and, like a soybean,

passed easily and readily into my abdominal cavity, a place where organs slowly

settled into the sediment like a solar system in aspic. Sludge metal and its symbols of stasis…

After the

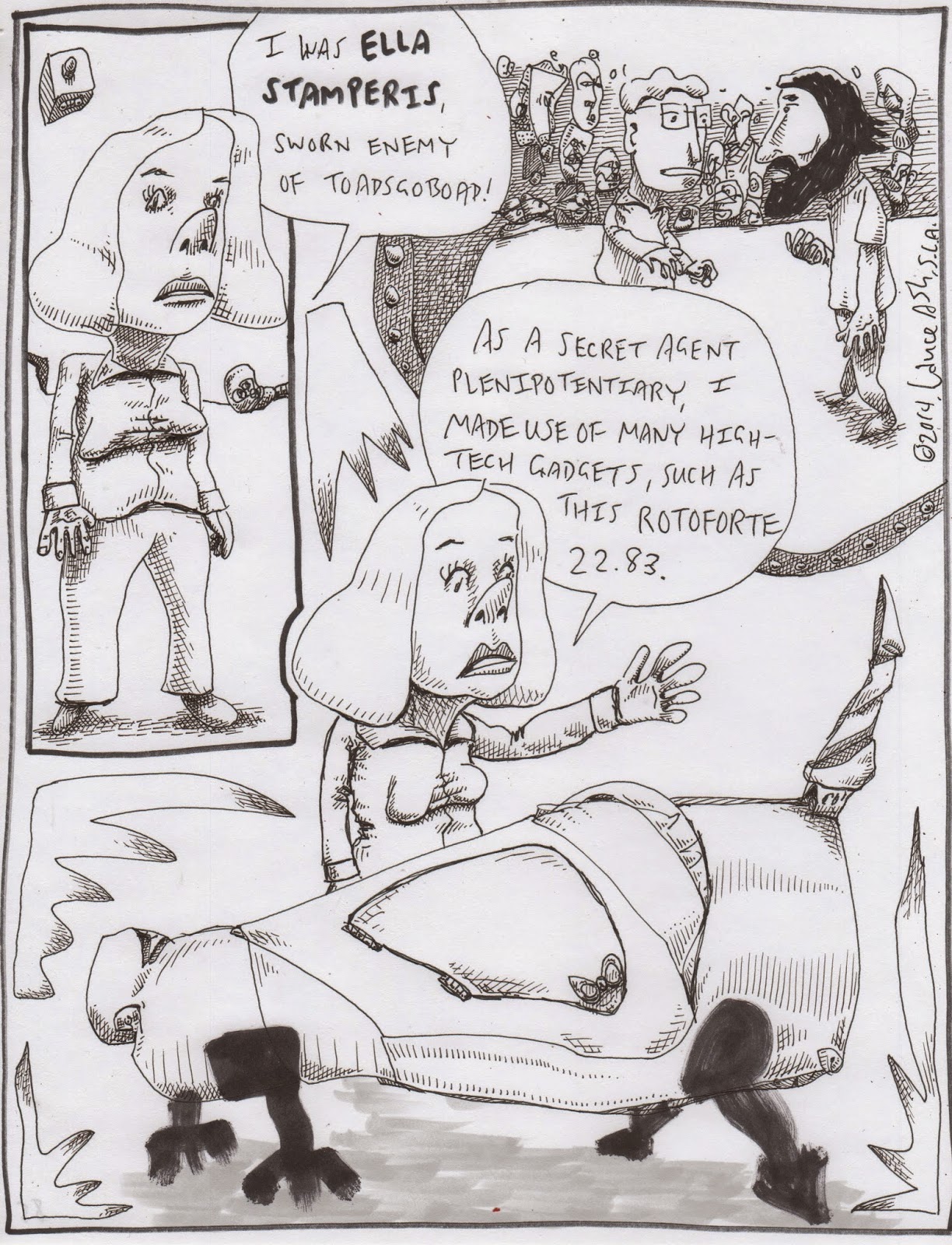

death of my semi-divine alter ego Toadsgoboad I was at a loss for some

time. I didn’t know how to go about

doing the things I had done under that name.

It was only after I realized that I was still Toadsgoboad despite reverting

to my birth name that I felt free to move forward. Of course, all the trappings of the

Toadsgoboad myth were gone, but the wider expanse of all existence was now

available. If I could but make use of

this source, my work would be the richer for it.

Ten years

earlier—I was listening to Swans and trying to penetrate its mysteries, trying

to familiarize myself with the material and master its burden. There were so many albums to work my way

through—and not just by Swans, but by dozens of other artists like Sonic Youth

and the Boredoms and Pere Ubu and Sixteen with the circle around the numeral.

Who knew

that I would revert to the telling of old-fashioned stories?

I Was Listening to Sonic Youth

I Was Listening to Sonic Youth & Contemplating Buying

a Lee Ranaldo Solo Album

“If ever

there can be truly such a thing as a solo album.”

“I take it

you don’t subscribe to the auteur theory then.”

“Decadence.” A voice from the back of the lecture hall.

“I haven’t

subscribed to anything in years. I think

the last thing was something like Juxtapoz

or National Review.”

“Two people

(essentially) just talking until they arrive at the truth, or at least

something interesting.”

“Henry

Miller said that he wrote to find out what he was writing about.”

“I don’t

care what Henry Miller said.”

“I don’t

give a shit what Henry Rollins has to say.”

“Blasphemy.”

“Decadence.” The same voice? Who was that?

I peered into the writing needs editing as much as painting does.

“You’re

supposed to say ‘darkness.’”

“I don’t

know exactly what I expected when I first started listening to Sonic Youth, but

I certainly didn’t expect to become intimately acquainted with ‘the

scene.’ I’ve never been a part of any

scene and I don’t think I ever will.”

“Unless

some group of admirers gathers around you like they did around Blake in his

elder years.”

“In the

digital age? Don’t fool yourself. Those days are over.”

“Perhaps if

you were to actually meet some people—“

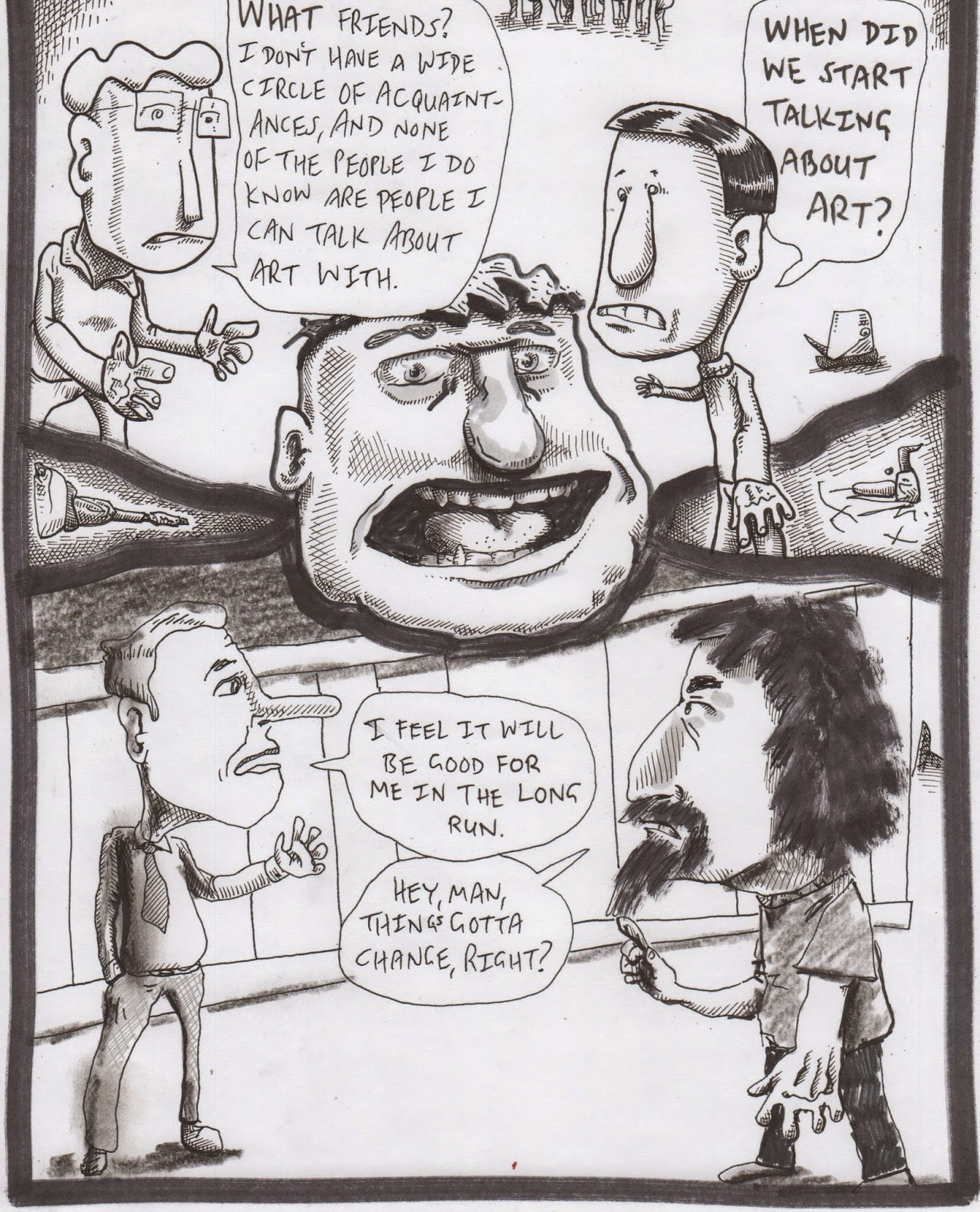

“My isolation

is complete. All the happy accidents

have already happened.”

“It’s all

luck.”

“It’s all

luck. The best thing I can do, the only

thing I can do, is to keep doing what I have been doing: spending every

available minute creating work that pleases me.

I must purge every remaining impulse to conform to standards of audience

appeal.”

“Branford

Marsalis won’t like it.” The voice; this

time closer, somewhere nearer the portable risers on which my fellow chorus

members and I stood.

“Your

references are dead. No one knows what

you’re talking about.”

“Kim Gordon

is available.”

“How many

female bass players named Kim?”

“No one

knows what you’re talking about.”

No

remembers a voice.

Winky Salamander and His Salami of Winkiness

Stars of red, white, and silver covered Nijinxi’s black

velvet pants. He stood on his hands and

urinated into the toilet.

“All too

easy,” he declared, falling onto his bare feet.

His shirt, which had gathered around his wiry shoulders during the

exhibition, now fell back into place, revealing the picture of Jean Dubuffet on

its front.

“Who is

that?” Bocamel asked, pointing to the image of the founder of Art Brut.

Nijinxi

flushed the toilet with a graceful tap of his slender fingers, nails painted

black. His penis, but a coracle compared

to the ocean liners that plied the currents of the sexual sea, withdrew into

the darkness to hide, writing poetry about flightless automatic birds that

stalked the disused soccer field behind the library.

“You

Americans with your ‘soccer,’” Lord Ewing sneered. “The rest of the world calls it football.”

All too

true.

If only

there was a literary equivalent to Art Brut.

And Thus Was the Man Deeply Enmeshed in Painful Self-Expression

Her Tender Skin, Her

Legal Appetites (They Frightened Me with Their Sincerity)

As in a Thermal Dance of Commitment

Each tear making its way down the course of her cheeks

contained a full crew of pilots, engineers, navigators, and technicians. When later asked about the difference between

engineers and technicians at a press conference in the band’s suite, I was

evasive.

“You must

understand that while I am regressing, a deep and abiding silliness hovers

about me like a cloak reluctant either to warm my shoulders or lend an

appearance of authority to me.”

“Why

must we understand this?” asked Little Joe, called the White Boy in Bologni’s

sadly overlooked comic strip.

I nodded;

the band, already confused by Jim Morrison’s presence, or absence, nodded in

return, committing themselves to nothing, but open to suggestions.

“Why don’t

you tell us about one of your many acquaintances?”

Chocolate

inconsiderate, up and down, wasting half his time in pointless socializing, the

mind no longer interested in much of anything besides the satisfaction of

physical needs and the avoidance of unpleasantness. My dreams are like an orange gymnastics mat,

providing a soft background for the day’s blind fumbling.

“He’s

really more a poet than anything else.”

What I am

is something I didn’t plan, didn’t expect.

The kind of painter, the kind of writer I am is apparently beyond my

control. I really have nothing to say

and yet I will say it anyway.

The Inside Mechanics of the Left Elbow and How it Hurts

A

smattering of interest in the old ways among the impatient festivalgoers

resulted in the publishing of Lord Ewing’s Nocturnal

Archie Shepp Wanderling, a collection of poem-like pieces accompanying

intricate diagrams of total bullshit machinery.

This alone was enough to enrage Harlem Infreque, one of the original

Nabiscope. The band now calling itself

Nabiscope has but a single member with any link to Harlem Infreque and the

other three originals. Such trivia

enrages you, you say? I can

understand. The Council on Foreign

Medicine has hired me to explain the similarities between Lord Ewing’s book and

that as-yet-unpublished by Infreque. Its

limited budget should not be squandered on lecturers who waste time with the

kind of details that only a fan would appreciate. However, before I go on, I must confess that

I am just such a fan. I even

still listen to whole albums. Well, I

try to. For example, just now, I skipped

a track on an Iggy Pop album. The song

didn’t specifically reference his over-rated penis, so I felt no need to

subject myself to it.

Of course,

the obvious similarity between the two books is that each is composed primarily

of short pieces of writing that resemble poems in many respects, accompanying

illustrations of objects which, although clearly machines, yet have organic

qualities. What is not so obvious is the

fact that both books are veiled commentaries on the life and work of Charles

Mingus. Harlem Infreque and his

bandmates often cited Mingus as a major influence on their own, nervously

gelatinous music (said to resemble a Danish youth bouncing around in his

folding chair at an early David Bowie concert).

Recent investigations by the Lost Eighth Percent Movement, the

enforcement arm of the Council on Foreign Medicine have discovered that Lord

Ewing also has a connection to the late bassist and composer: He is, in fact,

Eric Dolphy reincarnated as a white man, but without the sandals.

My own

analysis of the situation is colored by an indifference of orchestral

proportions as to whether or not anyone in this crowd of Danish youths and

professional colleagues and fellow fans of the Booger Metal genre, of which

Nabiscope was arguably its finest example, is persuaded of anything I might

have to say on this subject or related subjects. That being said, I must admit that I am

an analyst of situations just such as this, making my way from day to day,

enduring the pain and lack of full mobility with all the aplomb demanded of a

member of the Royal Society of Subjective Situation Analysts. My sunglasses, I’ve left them on the

piano! There they are in that archival

footage from some earlier festival, clearly visible between Bud Powell and a

trombone case. That trombone case, by

the way, doesn’t contain a trombone. No

telling what Eric Dolphy might have accomplished.

Not Even a Magnetbox Can Contain the Self-Conscious

Hexagram

No one knew

what to make of the diagram until Moof suggested we look at it upside down.

“It’s a

cake!” Chandra ejaculated. She ejaculated. She ejaculated her words like a

mighty, live-giving burst of seminal fluid crowded with wriggling

man-tadpoles. Several of us in the crowd

of diagram interpreters exchanged glances and juvenile grins.

“That’s

enough, that’s enough,” growled Captain Begottomy, pushing his way to the front

with his heavily tattooed paddlehands.

He stood with his snout only inches from the framed diagram. “I see nothing to snigger about,” he

commented. “It’s only a cake.”

“It’s not a

cake,” I objected. “It’s an

architectural machine.”

“Get your

minds out of the gutter, boys,” Captain Begottomy advised. His enormous, lumpy body was ambulatory only

with the help of the gravity-defiance suit.

“Do you

see?” I pointed to several details in the technical illustration. “It’s an architectural machine.”

“Why can’t

it be a cake too?” Chandra wondered.

“It can,” I

admitted. “But its general inedibility

negates any perception of cakiness in the mind of the average person.” I waved at the window, outside of which were

to be found these average persons.

“You’re all

a bunch of dirty-minded children,” Begottomy accused, whipping halfway around

in a gelatinous undulation to glare at us out of one eye. (He had four)

“Wait a

minute,” Palmeira begged. “Is this a diagram or a technical

illustration?”

“Well, technically speaking,” I later repeated

for the benefit of the committee, “It’s

a cartoon, but that’s only because its accompanying text forms a caption of

sheer meaninglessness.

“He and his hippie companions have only one thing on their minds:” the Captain delivered his testimony by way of sub-etheric wave transmitter. “Dirty, kinky sex with no intention of ever repopulating the planet.”

“He and his hippie companions have only one thing on their minds:” the Captain delivered his testimony by way of sub-etheric wave transmitter. “Dirty, kinky sex with no intention of ever repopulating the planet.”

PDOPD-97-100!

The Women of Elder

Diaphragm

When I

first proposed a tribute of sorts to the women of Elder Diaphragm, some of my

friends thought I was talking about the Deal Sisters. Perhaps I disabused them of this notion with

unnecessary heat, but their confusion seemed a humorous put-on, one calculated

to piss me off.

“I don’t

know what you got so upset about,” one of my friends, the one in the Opeth

t-shirt, later grumbled as we examined our vending options. “They smoke and they have brown teeth.”

“Hey!” I

snapped, causing my friend to push the wrong button. Instead of a bag of Funyons, he got some new

kind of potato chips apparently made with Kellogg’s Special K, judging by the

packaging.

Note: Kellogg’s has the sound of breakfast about it.

“It’s rare

that I find anyone in the… Arts,” I threw my hands out in deference to the

word’s imprecision and general lack of suitability, “That I both like and

respect—“

“I bet you

wouldn’t like them if you actually met them,” my Opeth friend interjected,

sniffing the contents of the incorrect purchase. Should he add milk?

I sighed,

more a huff, really.

“And even

rarer that it happens to be a woman,” I continued.

“And twins

at that,” Opeth man added.

I walked

away, leaving him to sort out his snack.

“So who are

these ‘Women of Elder Diaphragm,’” another friend asked as I puzzled over the

Pixies once again.

The story,

as told to me one crazy night when the number in the circle, taken as a

symbolic whole, corresponded to characters neither described as yet nor firmly delineated

as either real or fictional: “Sometimes,” the old man began, “A character can

be both real and fictional at the same time.”

“Bullshit! Bullshit!

Bullshit!” I screamed, running outside with my hands over my ears, loath

to hear such heresy.

Such looseness of form, a hallmark of MODERNISM, with all of its attendant evils, like stream-of-consciousness and amorality, was beyond my comprehension. I didn’t even know the difference between Kim and Kelley at that time.

Such looseness of form, a hallmark of MODERNISM, with all of its attendant evils, like stream-of-consciousness and amorality, was beyond my comprehension. I didn’t even know the difference between Kim and Kelley at that time.

.

.

.

.

PDOPD-supplementary material

Laser Fruitcakes Ignore the Omnibus

The beard

descending from Astercore’s left eye was a latticework of resin-reinforced

seaweed and twigs, containing platforms at regular intervals that provided

shelter for many of the onion rings now held in common by the Children of

Venable. Tarzan, with infallible

judgment, had built a small observatory on the uppermost of these platforms.

“Any lower

down and our vision would be obstructed,” he explained to an awestruck pair of

documentary filmmakers from several bodies away. Their newspaper, The Harbison Obsolete Medium, tasted bad unless you’d been raised

to appreciate such an exclusive focus on the tongue’s bitterness

receptors. Tarzan’s picture on the front

page would be seen as a naked ploy to win sympathy for the conservatives, but

current editorial thinking was that identification with the roots of popular

culture was worth the risk.

Arthur

Lamont, the journalist wearing glasses, was not wedded to his employer’s devotion

to antiquity. He had no qualms about

using a digital recorder to document the jungle lord’s comments. However, as Tarzan seemed to find the

technology frightening on a race memory level, Arthur was forced to scribble

down an approximation of what he heard.

The other

journalist, the one with the beard and hair parted in the middle, was Thurber

Turmek, officially the photographer on the assignment, but, as, again, Tarzan

did not understand and therefore feared the simplicity and miniaturization of

the camera Turmek proposed to use, he was left to wander around the

instrument-crowded platform, wondering if he could jump off the side and

survive unscathed, like on some cartoon.

Meanwhile

(and isn’t it always meanwhile with one person in one place and somebody

else in another?) Sunday Medson stood in the doorway of the bathroom of her

suite at the Whittington hotel and smiled at all of this novel luxury. She was more stoned than she had been in some

days, but that does not fully account for the intense pleasure she took in

looking at this boxful of furniture and décor.

No, what made it so deeply pleasurable, like the circular mental

satisfaction of an individual truism, was that this was all hers for free.

The Blad

Foundation, so went Sunday Medson’s cannabis-altered ruminations, chose the

wrong person when they chose me. I don’t

give a rat’s ass about their “mission” to present the historical legacy of the

days of the old religion. She frowned. That was something that could bring her

down. All that wasted time and

effort. Years ago. Years before her time. Damn, she felt she needed another hit off her

bong. But she needed to ration her

stash.

When Arthur

Lamont interviewed himself, his imaginary interviewer was a nondescript

journalist vaguely of the Kurt Loder type (during Loder’s MTV days), but

younger, and genuinely curious. He

usually sat next to Arthur in the car while Arthur drove and posed questions which

Arthur answered out loud. Had Sunday

Medson known this about the seemingly straight-arrow Arthur Lamont, she would

have been surprised. She might even have

offered him a joint, but his recent identification with the Blad Foundation and

espousal of its “beliefs” had made her wary.

Salvatore

Remmick, the imaginary interlocutor of Arthur Lamont, asked Lamont about his relationship

with Sunday.

“I knew her

in the old days, back…” he paused, indicated with his thumb the road already

traveled, “In the old place.” He

swallowed and thought hard. There was

always the possibility that Salvatore Remmick would interject something,

something perhaps presciently leading, but Arthur knew he would wait.

“We were

colleagues. We’re colleagues now. But,” he paused. “I don’t know if we’re closer now, despite

there being a definite, employment-mandated wall between us, than we were back

then or not.”

“So, she’s

just a co-worker,” Remmick tried it out.

Arthur

cocked his head to one side.

“Well, if

you’re asking does she, or does she not, figure as a… figure in my

self-conceived mythology, well then, I guess she would have to, wouldn’t she?”

Arthur admitted.

Remmick

asked, “What role or characterization does she fulfill? Or say, play, what role does she play?” He was a funny sort of person, now that you

had a chance to examine him. He didn’t

look like a fully fleshed-out human being, but rather like a comic

drawing. Maybe by Charles Saxon or a

funhouse version of Charles Schulz.

Arthur turned his attention back to the road.

Fingerless Gantry

En Route

Arthur had

borrowed the team’s car for the day. His

imaginary interviewer, whose name was that of an actual rock journalist that

Lamont had seen on some documentary, probably the Pixies, was, like his

namesake, a slightly overweight (at least by rock standards) man in his late

twenties or very early thirties who had enjoyed some modest success in his

hometown playing bass in a band called Slothful Cabarello and genuinely did not

care which gender of human he had sex with.

All of this, of course, was an unopened book to Arthur, for whom Salvatore

Remmick was really nothing more than a flickering image, coming into

corporeality beside him in the car, or floating in the aquarium of his mind,

across a poorly laminated table in a rock star’s hotel room.

“Keep your

eyes on the road, please,” Remmick advised Arthur with uncharacteristic

caution.

The

atmospheric subtleties of the quieter aspects of Caspar Brötzmann’s music. Can you imagine any icier art to accompany it

than the depictions of corporate success in 1980’s illustration? Even art depicting its contemporary

antithesis: the concrete and glass utopia of East Germany .

“You wish

you had been a rock star?” Remmick interrupted Arthur’s thoughts.

“I am

a rock star,” Arthur countered. “Or else

you couldn’t be interviewing me.”

“Yes, your

band, the Driblets, it’s mostly composed of persons such as yourself, your age

group, your income bracket, your level of actual experience in the music

business, isn’t that true?”

“You know,”

Arthur shook his finger, cooking up a retort of Krebs Cycle-like

complexity. “I don’t know if you’ve ever

heard of Nadar, he—“

“Yes, I

know who Nadar was. Late 1800’s,

photographer.”

“Good, I

won’t have to explain that. Well, do you

know what his Pantheon was?”

“For the

sake of moving things along, yes, I do.”

“Excellent. You are most helpful. Anyway, imagine all of those people in the Pantheon, almost all of them

writers. Think of all the journalism

created by those men. Most of that

newsprint, most of those words, still exist, they’ve been archived somewhere. You can go and find it and read it. And you know what?” Arthur demanded.

“99%

doesn’t amount to a hill of shit,” Remmick returned flatly.

“Oh, you’ve

heard this theory before?” Arthur looked taken aback, even as he deliberately

ran over a bag filled with someone’s Burger King remains.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)