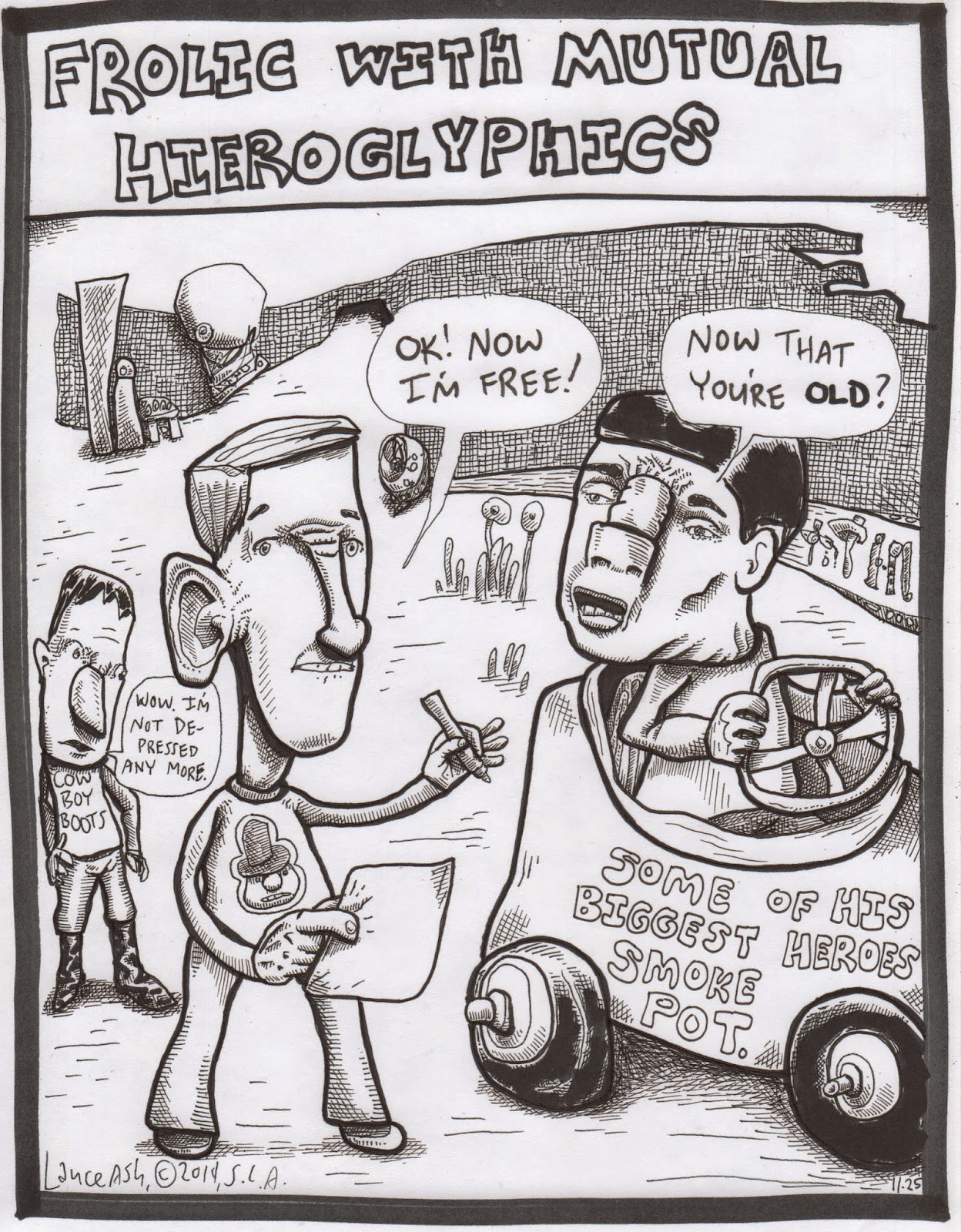

Frolic with Mutual

Hieroglyphics

Pigmented

frost saturated the sides of Mr. Lurie’s art project. As he and a crowd of assistants and

sycophants stood about, debating what to do to correct the situation, the

gallery’s curator, Mr. Moore, emerged from his office onto the catwalk

overlooking the gallery floor.

“Come take

a look at this,” he called to me, his forearms on the railing.

“He calls

it the Sardine Stethoscope,” Moore informed me. I carried my mug of fancy green tea out of

the office and joined Moore

at the railing.

“I’m a

hypocrite,” I told Moore . “As we all are, naturally. I resent such indulgent tripe even as I am

guilty of doing the same type stuff.”

“Surely you

can’t compare your work with this.” Mr.

Moore bounced his forehead towards the installation, which was a large,

fabric-covered box.

“If you

don’t like it, then why do you have it in your gallery?”

“First of

all, it’s not my gallery; I’m just the curator. Second, I like Lurie; he’s a good guy,

even if his art is crap. Third, he’s a

famous name. If a Mr. Lurie wants to

spend his time between albums doing this sort of thing,” again Moore used his forehead as an unobtrusive

index finger, “Then his work acquires value, even if it’s only the value of

notoriety.”

I felt that

my tea was cool enough to drink. I had

never tried Patriot’s Umbrella. It was

supposed to be good; at least, according to an article in Samsasamsara magazine that

someone had told me about.

“How is

it?” Mr. Moore asked, smiling at my face of disgust.

“It has

tremendous snob appeal,” I replied, so tempted to dump the rest of my mug onto

the Sardine Stethoscope that I had to

cast my mind into a reverie to stop myself.

Ten years

earlier I was working at the Post Office, hoping that the facility I worked at

wouldn’t be shut down and my job transferred to a larger one in Atlanta , necessitating a

one-way commute of two hours. There

were those that I worked with who didn’t care if we were all shipped off the Atlanta : they either lived

in rental properties and could easily move closer to work or they didn’t have a

multi-faceted art career demanding a couple hours’ attention every day as I

did. I was a painter, a writer, a

cartoonist, and a musician. I felt that

everything depended on the maintenance of the routine I had established. Without my art, the many things that I did,

my life would be empty. I might as well

start going to church or take up drinking again.

Ten years

earlier the sunburst medallion given to me by the Fromme Emperor shrank to the

size of a soybean under the glare of the roadside halogens and, like a soybean,

passed easily and readily into my abdominal cavity, a place where organs slowly

settled into the sediment like a solar system in aspic. Sludge metal and its symbols of stasis…

After the

death of my semi-divine alter ego Toadsgoboad I was at a loss for some

time. I didn’t know how to go about

doing the things I had done under that name.

It was only after I realized that I was still Toadsgoboad despite reverting

to my birth name that I felt free to move forward. Of course, all the trappings of the

Toadsgoboad myth were gone, but the wider expanse of all existence was now

available. If I could but make use of

this source, my work would be the richer for it.

Ten years

earlier—I was listening to Swans and trying to penetrate its mysteries, trying

to familiarize myself with the material and master its burden. There were so many albums to work my way

through—and not just by Swans, but by dozens of other artists like Sonic Youth

and the Boredoms and Pere Ubu and Sixteen with the circle around the numeral.

Who knew

that I would revert to the telling of old-fashioned stories?